Special feature: Gotha Research Library presents Martin Luther's translation of Jeremiah in the original

Manuscripts that early modern authors submitted for printing are rarities. This is mainly because the manuscripts were often taken apart during typesetting and disposed of after publication. Nevertheless, many fragments of the English translation of the Bible by Martin Luther and his Wittenberg colleagues have survived. This is due not least to the already contemporary interest in collecting autographs by Luther and other reformers.

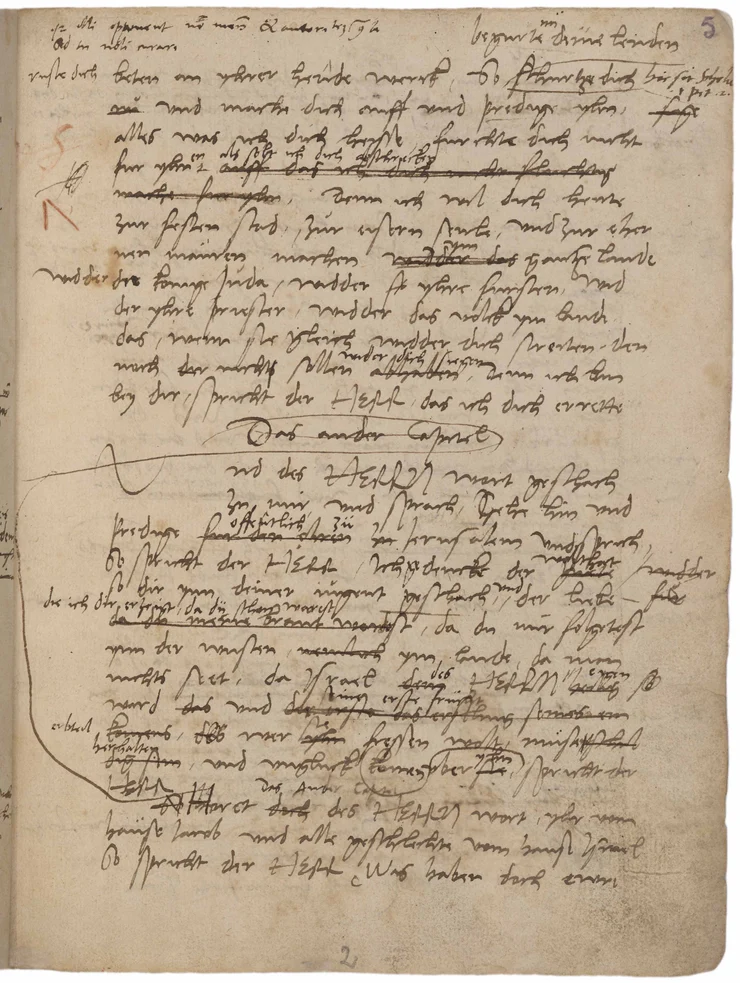

Not a single line of the New Testament has survived in Luther's hand. Parts of Old Testament books are preserved in various archives and historical libraries in Germany, Poland and Denmark. The manuscript of the Prophet Jeremiah printed in Luther's own hand is now in the Gotha Research Library. The manuscript, comprising more than 80 leaves, represents almost 15 per cent of all surviving manuscripts of the Bible translation. The fragment passed through several hands, including that of the important Dresden court preacher Matthias Hoë von Hoënegg (1580–1645). In 1719, Duke Friedrich II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1676–1732) finally acquired it from the Leipzig bookseller Thomas Fritsch (1666–1726).

"Such printed manuscripts provide unique insights into the translation processes and philological practices of how universally understandable, English verses were formulated from Hebrew and Aramaic texts," explains Dr Daniel Gehrt, research employee for the indexing of early modern manuscripts at the Gotha Research Library. The many corrections, changes in the choice of words and rephrasings testify to the persistent efforts to reproduce the Holy Scriptures as faithfully as possible in terms of words and meaning. The page from the prophet Jeremiah shown here vividly illustrates the complex process of creation. "It is almost surprising that everything could be correctly typeset without first putting the manuscript into fair copy. The text of the first edition, however, corresponds to the wording of the manuscript and the typesetter's red margin marks exactly match the page breaks in the print."

The printing of this monumental work was crucial to the realisation of the Reformation demand that the Bible be made available to a wider public in the vernacular. Nevertheless, not all lay people who knew how to read could afford their own copy. The translation was especially intended for clergymen who, in sermons and catechesis, orally transmitted passages of the Bible word for word according to this translation, which quickly became canonical.