Accidental Occidental traces from a perhaps pre-Brexit London, found there in the last weeks of 2018 and laid on a Berlin table

there read in terms of a perhaps “crisis of the West”, seen from an anti-authoritarian perspective, and journalistic symptomologies based on this

// Holt Meyer – 11.01.2019

The idea

At the end of the eighth year of the 21st century’s second decade, “the West” – if defined in terms of democracy and the rule of law – once again seems to begin and end in Russia, for Russia and with Russia.

I mean by this Russia’s seemingly natural alternative position and its adversarial pose vis-à-vis the “West”, a running occidental pleasantry of the last 150 years or so. What is more or less new in the current version of Russia’s automatic ‘anti-occidentality’ is that it is in a bizarre manner and for the first time in at least 70 years unopposed by the Unites States government, the supposed ‘leader of the West’ which now appears to have abdicated from this role.

This non-opposition is said to be creating the latest “crisis of the West”, as MSNBC put it in early June 2018. It is also creating a rift with Britain, which is, in turn, in the middle of a “divorce” proceeding with the EU. That is the one “West” the one everyone thinks of in terms of “current events”.

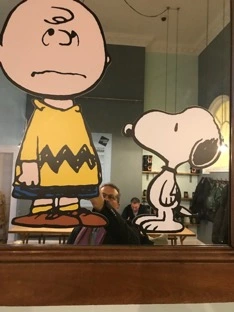

On the other hand, “the West” in the form of the London presence of Charles Schulz’s Charlie Brown and Snoopy, that is, Peanuts, is going strong. This is shown by the self-evidence with which an American comic strip occupies a huge space in the Somerset House in the middle of the British capital, in a exhibition called “Good Grief Charlie Brown”, which is adjacent to sumptuously appointed selling spaces of the iconic English comestibles-purveyor Fortnum and Mason, and, during the winter season, to a skating rink (reminding us of the opening skating scenes of the 1965 television classic “A Charlie Brown Christmas”).

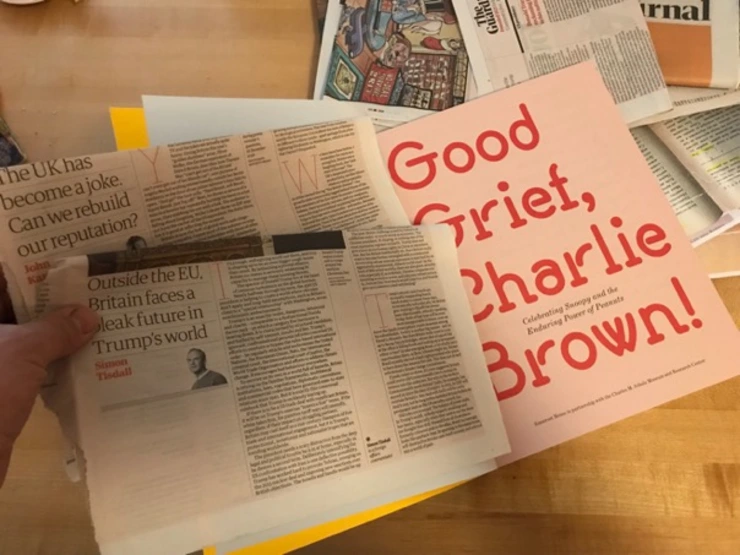

It is the coincidental and non coincidental, accidental and occidental finding of these traces in the same place, London – arguably a crucial node in the spatio-temporal network one assumes to be “the West”, leaving open the question of whether there is such a thing in ‘reality’ - at the same time which is the subject of the first West-Window. Its points of departure are four objets trouvés. The choice of these four is based on the need to read the signs of the times and to find a method for doing this in terms of a ‘West-claim’ which I try to look at through this West-Window.

The material

They are summed up in a collage (objet 0), made on 08.01.19, at a dining room table in Berlin.

Seen from Berlin, the continued openness of the Brexit question just over two months before the deadline is unnerving, but the open-endedness and a certain cultural territory’s (in)ability to deal with it without panic and predictions of doom are also a window to a particular vision of “the West”.

I pass no judgement on this, but rather simply put it “out there”.

Introduction: Bellingcat and an Iconic Dog

The two articles held in (my) hand in the Berlin image are from England and about England, but their arguments depend on a crisis of “the West” which is unthinkable without (and deserves the name “crisis” because of) Russia - as the power which seems most likely to exploit and/or try to create an occidental crisis. The middle link in the chain, objet 2, the one which explicitly addresses the “the West”, presents us with a map delineating Europe’s edges as the place where the fate of the center is decided (reminding us of Yuri Lotman’s analysis of the relationship of center and periphery, which, in the end, was in its context mainly an analysis of Russian history).

One of those edges (perhaps “corners” is the better image) is Ukraine in the southeast, another is Britain in the northwest.

And then there is Salisbury, West-Southwest of London: the association emerges out of the interface between Russia and England being irreversibly framed within the drama surrounding the Skripal murder attempt and the senseless death of Dawn Sturgess in July 2018.

And finally there is Natalia Antonova, author of the piece. On the same day the article appeared she tweeted: “Fear and exhaustion are part of the authoritarian toolkit. That's why Putin likes them, and why Trump wants to inflict them on you.”

And here Antonova is aligning herself with a vision of the “West” which is anti-authoritarian, indeed which has learned the lesson of having in the past been subjected to the “authoritarian toolkit” and concentrates its energies on that’s not happening again. She does it by reading signs of the times and passing them on, and here, I am passing on this passing on as a window to “the West”.

Charlie Brown and the Performance of “Western Values” in the 2nd half of the 20th Century

A comic strip, originating in the 1950s, which never visually shows parents or teachers, indeed not a single adult, only children. Who can deny in retrospect that the attempted alliance of the “West” with the anti-authoritarian also begins here?

It begins also with “Peanuts”, with Charlie Brown, the hero of the exhibition in Somerset House, which is there from October 2018 to March 2019, the month of the projected Brexit.

https://www.somersethouse.org.uk/whats-on/good-grief-charlie-brown

Sections of the exhibition which discuss “Peanuts and Existentialism”, “Peanuts and Feminism”, “Peanuts and Psychiatry” and other like topics catapult the comics into intellectual heights - heights, as the texts in the exhibition document, in which the creator Charles Schulz claims not to have felt comfortable. This may have been his read opinion, may have been an expression of his extreme modesty and/or scepticism vis a vis authority, but also – forgive the cynicism – might have been part of Schulz’s image cultivation aimed at not scaring off the less educated members of his audience. For the genius of “Peanuts”, as the exhibition in Somerset House shows and the texts state on many occasions, didn’t just happen by itself.

Be that as it may, the 60s, the time when the true genius of “Peanuts” emerges, is a time when (the gesture of) questioning authority becomes a general Euro-American trend, extending even to Czechoslovakia, also the only East Bloc country which seriously tried to accept the Marshall plan, and in many ways the most ‘Western’ of them all. As Tony Judt notes in his Postwar, the actual political context of the movements of the 60s was more superficial than it seemed at the time, but “Peanuts” brilliantly expresses the trend of self-questioning which engulfed ‘Western’ thought at the time. “Peanuts’” presence at the Somerset House also underscores the very particular US-UK link within the ‘West’, expressed by the transfer of the Beatles, the Stones, David Bowie, and Led Zeppelin to the US and enthusiasm in Britain for American post-war culture, exemplified in phenomena from “Peanuts” to the TV series “Friends”, whose popularity in the UK is unbroken over the last 20 years, despite its being heavily centered on a 1990s Manhattan setting.

Both of these examples feature young people among themselves, with very little presence of older figures of authority, a staple motif of the self-representation of the ‘West’ in the last 60 years at least.

The Fate of the West Decided on Europe’s Edges (England and Ukraine)

Objet 2: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/nov/27/putin-ukraine-sea-of-azov-russia

Russia (as the ‘West’) as the self-named shepherd bringing back ‘its own sheep’ who Soviet and/or Russian officialdom deems to have strayed too far ‘westwards’ is also a post-war historical staple. The case of Czechoslovakia 1968 was already mentioned. The latest significant example of this tendency is Ukraine 2014 till now, a half a century later. Here too, Russia offers its services as a counterweight to ‘Westernism’.

I take up this article, also on the Guardian opinion page, this from a month earlier, to contextualize the year-end discussions, also concerning the relations between the USA and the UK as a further symptom of a “crisis of the west”.

In Antonova’s article, the “crisis” is located in the “west”’s inability or unwillingness effectively intervene on behalf of Ukraine to help defend itself against Russian interference and aggression. I cannot discuss this issue itself here, although it is eminently relevant, but rather will stay with the narrower scope of my comments: ‘occidental’ traces found in the UK.

Antonova as accounced as an editor of Bellingcat, the organization which, among other things, uncovered the real identity of the two men who poisoned Yuri Skripal and inadvertently murdered Dawn Sturgess in the town of Salisbury.

All of this could and should be material for extensive comment. But let’s keep it short.

The key phrase for the topic at hand is:

“Ukrainian victims of the conflict are largely treated as irrelevant in the west – and those traditional foes of Russia are divided and demoralised. Britain is gripped by Brexit woes. Over in the US, the authoritarian demagogue in our White House refuses to condemn Russia’s actions.”

The “west” is defined as “traditional foes of Russia”. The individual “Western” countries named are the Brexit-plagued UK and the demagogically ruled US.

Taking a step back, I note that two things:

- Unperturbed by all these “woes”, Charlie Brown continues to reside in the Somerset House until March 2019. He is a boy of woes himself, but he represents a ‘Western trend’ of self-reflection, be it existentialist or not, which dates back a half a century. The US visits the UK in this form as well.

- These comments from England touch on a geographical field which is seemingly beyond the borders of ‘East’ and ‘West’, they can be read as seen from one ‘edge of Europe’ to the other, since the UK appears to be drifting out of the ‘European orbit’. This is the subject of the fourth and fifth items, objet 3 and objet 4.

Can we, How Will We Rebuild

Objet 3: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/25/brexit-uk-global-joke-rebuild-reputation

Seen from the Berlin kitchen table, the first line of this article is particularly evocative:

“You know you’ve hit rock bottom when the Germans mock you on primetime TV and the jokes are actually quite funny.” And of course also: “Germany frets about life after Mutti Merkel.” This becomes especially telling in the days and hours before decisive Brexit votes in Westminster on January 15, 2019.

The broader sweep further along in the article is worth noting:

“Britain is now the butt of global mirth and cringe-making sympathy. I spent most of this autumn on trips trying to link our creative industries with those of other countries. From Mexico City to Montreal, Amsterdam to Tallinn, the welcome starts with the avuncular hand on the shoulder, a sigh and a reference to “our British friends”, followed by “I hope you’re all right””.

The four cities mentioned align themselves in different but distinctive ways with the “West”.

The link to the broader topic in my comments and to the “West” is the hinge between the last and next-to-last paragraphs: “Vladimir Putin is working his way through Europe, fomenting extremism. // Whatever transpires with Brexit, the British brand is tarnished.”

There he is again, Putin (though thankfully not as a representative of all of Russia as a permanent enemy of civilization). And again: the east and west edges of Europe brought together in an imagery of “tarnish”.

Most interesting though, as a year-end snapshot: the evocation of the 1970s, and the fear (and hope) that after a generation, Britain (and Europe, and the world, maybe even Russia) will be on course.

Outside the EU

Objet 4: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/26/eu-brexit-trump-world-us-president-europe

The last found object commented on here evokes the calamity of Trump in times of Brexit, seeming to be the total opposite of the allignment of English and American culture in “Peanuts”. The drastic image is unfortunately not inaccurate:

“Trump’s is an anarchic realm, dangerous, delusional and chaotic – comparable to a dysfunctional Florida theme park – on which a category five hurricane is bearing down. It is characterised by structural vandalism, and fuelled by self-interest, insults and lies”.

And look who pops up again in the context, this time even with a photograph:

“Russia is a leading beneficiary of Trump’s contempt for western solidarity and shared values – and a big problem for Britain no-mates. Vladimir Putin poisoned at will in Salisbury, subverted the Brexit vote, and regularly violates British sea, air and cyberspace. His covert hooliganism extends from the Barents Sea to the Sea of Azov. Russian “malign activity” in 2019 will underscore the reality that, in or out, Britain’s external defense and security remain intimately linked to Europe’s.”

“Western solidarity” appears again on the horizon – as an object of Trump’s shameful “contempt”. And we are back to Salisbury and Ukraine, back to the Sea of Azov addressed by Antonova, back to the edges of Europe. The point stressed in this case is that, Brexit or no Brexit, the UK will need Europe to maintain “the West”. The article’s anti-Americanism – at least as concerns Trump’s USA – is, sadly, well-argued and hard to refute. Here too, it might take decades to recover from this: to clean a dusty window through which everything looks so dark, to polish its tarnished lashes.

Perhaps it is best, despite everything, not to lose our sense of humor and good old English self-irony.

Through the Looking Glass

At the time of the writing of this text, the UK entering a decisive phase of its Brexit conundrum, and the US president seems to be falling further and further down into a rabbit hole. The Guardian asks “how will we rebuild” and casts a worried look at a UK drifting away from the EU and towards a USA enmired in political calamity and at best paralyzed in its role to defend “the West” in its “traditional” enmity towards “Russia”. Just what is “traditional” about this enmity and what exactly is that “Russia” – Putin’s Russia? every Russia imaginable at all times and in all forms? – is not clear.

There is a certain absurdity to the situation, since none of this seems absolutely necessary and could be turned around by a few turns in the political process of the coming months. Many who view themselves as belonging to the “West” seem to be clinging to a number of narrative security blankets in order to define it (the word, associated with Linus from “Peanuts”, entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 1981, as a text from the exhibition “Good Grief Charlie Brown” and page 40 of the exhibition catalogue proudly note). One of them is the eternal enmity of Russia, and perhaps the position of America is also shifting. It might help to take a bemused distance from these and other narrative fixations in order to overcome them.

Looking at the ensemble of English traces on a Berlin dinner table, I allow myself a final comment: This version of a West Window resembles to a certain degree “Through the Looking Glass”, the soon to be 150 year old sequel to “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. It shows us manic figures who seem to be derived from a Lewis Carol plot which makes them all the more absurd in their repetition.

Perhaps we shouldn’t miss the chance to laugh at this and ourselves while looking through this version of a West window – indeed, in the spirit of Charles Schulz’ rightly celebrated “Peanuts”.