Documenting Ancient Coins

The ancient coins on the table in Titian’s famous portrait of Jacopo Strada shows that he considered collecting and studying coins an essential part of his role as “Antiquario della Sacra Cesarea Maestà”, official antiquary to Emperor Maximilian II. Of course, Strada was not the first erudite humanist or artist to collect and study these exciting, easily portable and – when in bronze – often relatively affordable collector’s items. With ancient inscriptions, they were particularly valued because they provided the only authentic written sources on ancient history: all the other written sources even of the most illustrious ancient authors, had been preserved only by repeated copying during the Middle Ages, which inevitably shed some doubt on their reliability.

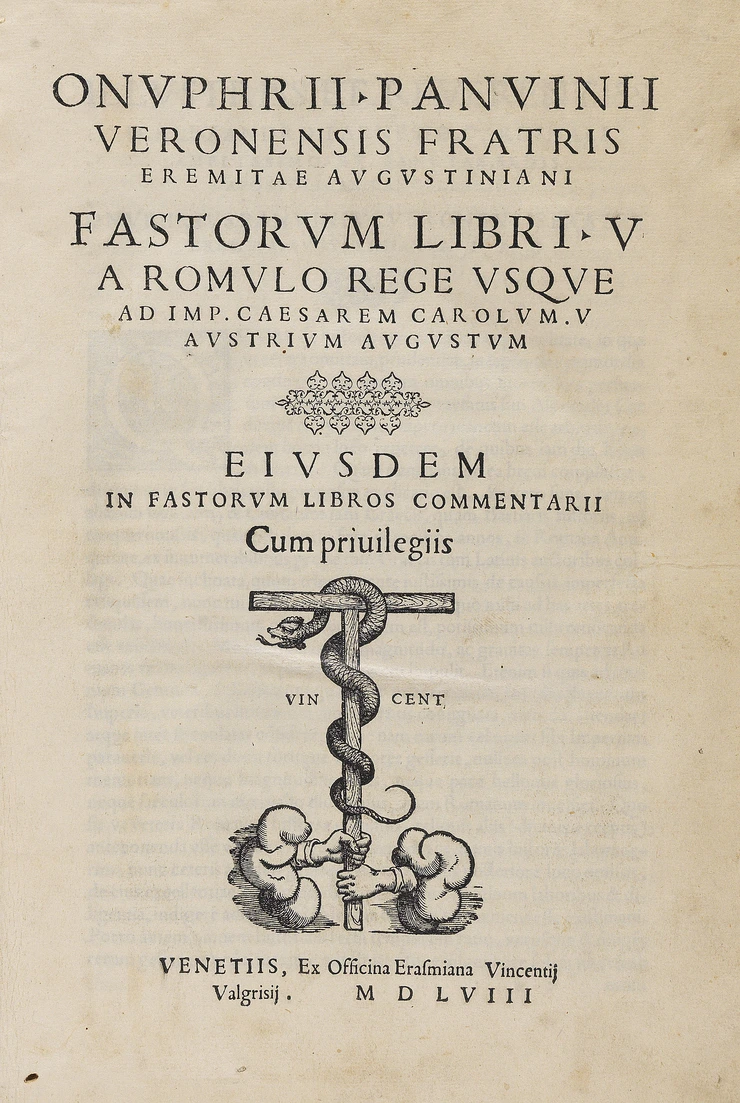

Coins and inscriptions could only serve as a source of information, when they could be interpreted in the context of the literary sources available – easiest in the case of coins in which the issuing authority – a Greek King or city state, a Roman Consul or Emperor – was named in the legend. Even then reference to comparable data was necessary. Thus, identifying consular coins became a lot easier, once a huge inscription listing the state calendar of the Roman Republic was excavated at the Capitol – whence its name, the Fasti Capitolini – and studied and published. Strada financed and organised the publication of one its earliest editions, printed at Venice in 1558, though (not to the satisfaction of its editor, Onufrio Panvinio.

In the case of Roman Imperial coins, the situation was somewhat easier, since lists of ruling Emperors had always been available, and they had been published at least since the early sixteenth century, often with added portraits, and directed at the general public as much as at humanist scholars. The popular Nuremberg Meistersinger Hans Sachs had published such a list, celebrating each ruler in one of his typical quatrains. Such lists always ended up with the name and the image of the ruling Holy Roman Emperor, in Sachs’ case Charles V, reflecting the theory of the Translatio imperii, according to which the authority of the Roman Emperor had been transferred to the Germanic successors of Charlemagne.

Strada’s own printed treatise, the Epitome Thesauri Antiquitatum, still conforms to the type: it consists of extensive biographies of each Emperor, placed in chronological order, and accompanied by a woodcut illustration derived from the obverse of a relevant ancient coin.

For his treatise Strada could draw upon a wealth of material he had collected in the preceding decade, when he travelled in Germany, France and Italy to collect material for the numismatic corpus. His first-hand documentation has not been preserved, but this must have consisted of the authentic coins of his own collection, and the quick sketches, casts, imprints or rubbings of, as well his notes on the coins he had studied in other collections. This was the material from which he developed both the designs for the final finished drawings of the Magnum ac Novum Opus and his other numismatic manuscripts, and the descriptions included in the ΔΙΑΣΚΕΥΗ.