Additional sources: Inventories, descriptions, references

References and Descriptions of the Magnum ac Novum Opus and the Diaskeuè in Strada’s writings

- Preface to Epitome thesauri antiquitatum, Lyon 1553

- Entries in Strada’s proposal to Christophe Plantin

- Entries in the Index sive catalogus, Strada’s list of planned publications

Several copies of Strada’s Index sive catalogus, the list of books which he intended to publish, and for which he attempted to obtain funding or other assistance from his various patrons, have been preserved: he moreover paraphrased it in several of his letters. A list of copies and paraphrases is given below. None of the fair copies of the complete Index are in Strada’s own hand: they were written by one of his sons or by a scribe he employed.

The following transcription is based on the copy preserved in Cod. 10101 in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (item A1). The item numbers in the transcription are added by the editor. This copy concludes with two items that were obviously added as an afterthought, but which are entered nonetheless in all the other complete versions we know. This indicates that it can probably be considered as the ‘master copy’ from which later versions were derived. When relevant, variants in other versions have been noted. This copy also adds a long list of other manuscripts in Strada’s possession, that probably were not part of Strada’s publishing project, but which he may have considered selling to interested parties (not transcribed here).

The excerpts given here are adapted from Dirk Jacob Jansen, Jacopo Strada and Cultural Patronage at the Imperial Court: The Antique as Innovation, Leiden/ Boston 2019, 2, Appendix D, pp. 902–914

<..>

[ 4 ] Alius liber de omnis generis etnicis et antiquis numismatibus aureis, argenteis et aereis, quae passim in universo mundo inveniuntur, et ego magnis impensis et cura acquisivi, quae latine in XI voluminibus descripta sunt. Et hac numismata partim ipsemet et apud me habeo, sicuti fabrefacta et excusa sunt; partim ipsemet manu mea delineavi ex ipsis numismatibus veris passim estantibus apud antiquitatum studiosos et viros primarios. Suntque eorum quae descripta sunt novies mille; et inter haec multa peregrina, utpote latina, graeca, hetrusca, arabica et aphricana variis characteribus et literis insignita, prius apud nos non visa et conspecta.

[ 5 ] Liber latino idiomate summa cum diligentia de novo et integro compositus et conscriptus de romanis imperatoribus, qui nunquam ante in lucem aeditus est. In hoc ante vitam ipsam uniuscuiusque caesaris videre est numisma eiusdem imperatoris, exprimens et representans ipsius effigiem; et quoque figuram alterius, sive posterioris monetae partis, in magnitudine taleri; quae numismata typis aeneis incisa et excusa sunt. Et quidem haec omnium pulchriora sunt, quae ab uno quoque imperatore habere potuimus. Et incipit hic liber a C. Julio Caesare, et finitur in nostro nunc rerum potiente imperatore Rodulpho huius nominis secundo. Apud et post cuiusque imperatoris vitam sequuntur eiusdem uxores, liberi et cognati, si quos habuit, et nos nomina eorum indagare potuimus; nec non tyranni, qui sub eodem imperatore vixerunt, et imperatoris nomen sibi sumpserunt, una cum eorum numismatibus. Et harum vita quoque succincte descripta est.

[ 7 ] Liber alius manu mea delineatus de numismatibus antiquis, in charta maiori, ubi in quolibet folio numismata XII, cum eorum aversis partibus visuntur. Incipiunt ista in C. Julio Caesare, et desinunt in hoc nostro romano imperatore Rodolpho secundo. Et ad finem istorum numismatum apposita est uniuscuiusque descriptio, una cum vita ipsius, sicuti antea dictum est.

<..>

[ 18 ] Liber complectens vitam et res gestas Caroli V invictissimi imperatoris, secundum veterum rationum et formulam compositus, una cum numismatibus, quorum sunt CL numero.

<…>

[ 49 ]

Liber de romanis, graecis et germanis imperatoribus et augustis omnibus, nec non de tyrannis cunctis, qui unquam contra legitimos caesares augustosque imperium romanum, vel vi et armis, vel fraude ac insidiis, occupare et accipere conati sunt. Additis etiam ipsorum imperatorum et caesarum, atque tyrannorum uxoribus, utrusque sexus liberis, et cognatis proximis. Estque hic liber integra et continuata series, historiaque locupletissima a Caio Julio Caesare incipiens, ac in Rodulpho II, Romanorum augusto, nunc rerum potiente, desinens. Insertae sunt ipsorum imperatorum effigies, partim delineatae, partim descriptae exactissima fede ex antiquis marmoribus ac archetypus, tum ex aeneis, argenteis et aureis numismatibus. Insertae sunt res plurimae scitu et cognitione dignissimae, nempe de magistratibus romanis variis, de multis ethnicorum diis, sacris, sacrificiis, templis ac operibus publicis, ludis et spectaculis romanis, ac animalibus peregrinis. Appositi triumphi, ovationes et consulatus caesarum, augustorum ac tyrannorum consulumque, si quae habere potuimus, numismata. Addite convenientibus locis variae antiquae inscriptiones, vel ipsorum imperatorum, vel consulum, vel rerum historiarum mentionem facientes. Insertae praeterea sunt suis locis multae figurae conflictuum et proelionum Romanorum tam contra hostes, quam inter ipsos cives et imperatores ac tyrannos gestorum. Additae item figurae castrorum in vicem oppositorum, [....?]mque munitiones; itemque urbium obsidiones et expugnationes, civitatumque ipsarum situm exprimentes, et oculis subiicientes. Accesserunt item locorum provinciarum regionumque inscriptiones et tabulae cosmographicae iustis locis adhaerentes. Adiecte sunt et leges ac rescripta ab uno quoque imperatore edita et promulgata. Omnia ista a nobis summa fide, industria et diligentia, maxime sudore et labore, ingentibusque sumptibus composita et collecta, sicuti opus ipsum, cuique rem ipsam, satis

References and Descriptions of the Magnum ac Novum Opus and the Diaskeuè in Strada’s correspondence

- Passages from Strada’s correspondence relevant to his numismatic works

- Jacopo Strada to Ferdinand I, King of the Romans; Nuremberg, 12 February 1558

Vienna, ÖNB-HS, Cod. 5770, f. 1r.–1v.; autograph (request presented in person) - Jacopo Strada to Hans Jakob Fugger in Augsburg, Vienna, June 6th 1559

München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cod. Monac. Lat. 9216, f. 3–4; autograph - Strada to Jacopo Dani, Secretary of the Grandduke of Tuscany, Vienna, 17 June 1573

Florence, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio d'artisti, I, ff. 126-127 - Jacopo Strada to Hans Jakob Fugger, Vienna, 1 March 1574

München, Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Kurbayern, Äusseres Archiv, 4579, ff. 69-70; autograph;

Published in Hilda Lietzmann, ‘Der kaiserliche Antiquar Jacopo Strada und Kurfürst August von Sachsen’, in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 60 (1997), 377–399 - Maximilian II concedes a privilege for a number of publications planned by Strada, Vienna, 30 May 1574

Vienna. Haus- Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Reichsregesten Maximilian II, Bd. 17;

Partially printed in Strada’s edition of Sebastiano Serlio’s Settimo libro dell’architettura and his edition of Caesar’s Commentaries, both Frankfurt 1575; published in Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen 13, 1892, II, p. LXXIX, Regest nr. 8979 - Strada to Jacopo Dani, Secretary of the Grandduke of Tuscany, Vienna, 11 July 1574

Florence, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio d'artisti, I, f. 128 - Strada to Jacopo Dani, Secretary of the Grandduke of Tuscany, Vienna, 9 September 1574

Florence, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio d'artisti, I, f. 130 - Ottavio Strada to Jacopo Strada, Nuremberg, 5th December [?] 1574

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Handschriftensammlung, ms. 9039, ff. 112-113;

Published in Dirk Jacob Jansen, Jacop Strada and Cultural Patronage at the Imperial Court: The Antique as Innovation, Leiden/ Boston 2019, 2, Appendix A, pp. 887–891

[Note: This letter is dated 5 Settembre, but since Ottavio replies to a letter of his father's dated 13 November, the correct date must be 5 December 1574] - Strada to Francesco I, Grandduke of Tuscany, Vienna, 4 October 1577

Florence, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio d'artisti, I, f. 138; autograph - Strada to Jacopo Dani, Vienna, 2 November 1581

Florence, Archivio di Stato, Carte e spoglie Strozziane, Ia serie, 308, ff. 63-ff.; autograph; enclosure (a copy of the Index sive catalogus... , see below) - Emperor Rudolf II concedes a privilege for a number of books that Strada planned to publish, Prague, 5 December 1584

Vienna, Haus- Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Reichsregesten Rudolf II, 4, ff. 512-514; published in JdKS 13, 1892, II, Regest nr. 9360

Prommer's Calculatio (1566)

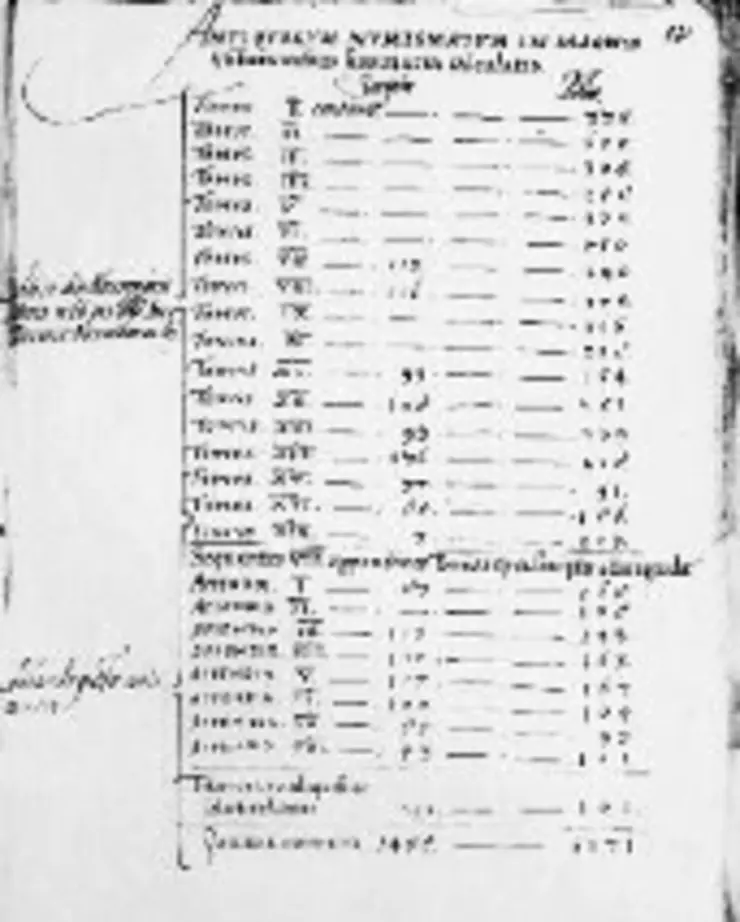

The unfinished state of the Magnum ac Novum Opus can be explained by the financial difficulties encountered by the patron, Hans Jakob Fugger, in the mid-1560s, which led to his personal bankruptcy. By that time, Fugger had become a councillor and intimate friend of Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria, who extricated him from his difficulties, paying his debts in exchange for Fugger’s collections, which included his enormous library and the Magnum Opus.[1] In the autumn 1566, during the course of the implementation of this arrangement, Wolfgang Prommer, Fugger’s librarian, made an inventory of the volumes as then present in Fugger’s Augsburg house, Antiquorum numismatum in magnis Voluminibus calculation; see here for a transcription.The term “calculatio” indicates that its primary function was to help establish the corpus’s monetary value in the context of the sale of Fugger’s collection to Duke Albrecht, and perhaps to calculate any outstanding compensation still due to Strada.

Prommer’s inventory listed nineteen volumes or albums of drawings. These were probably portfolios, the contents of which were as yet unbound but were already organized in chronological order. The first sixteen volumes contained drawings of Roman imperial coins from Julius Caesar to Licinius, and must have been considered sufficiently complete, since they were sent to Munich on 25 October 1566. Three further volumes are listed: volumes 17 and 18 were empty of content; they were probably intended to include the coin drawings of the later emperors, at least up to the Fall of the Roman Empire, which appear not yet to have been selected or produced at the time. Volume 19 was an additional volume presenting drawings of coins of empresses and other female dependents of diverse emperors.

In addition, Prommer listed a further eight Appendices, again unbound portfolios, in which a number of additional drawings were collected: these were intended still to be inserted into the existing portfolios. Finally, he lists a folder (“fasciculus”) of 137 loose, “redundant” sheets, which may have been duplicates. His total calculation comes to 7659 sheets, 6171 of which were “paginae pictae”, i.e. drawings, and 1488 “scriptae”, i.e. sheets where the coin was represented solely by the legend, omitting the image.

Since vol. 15, including Hadrian’s coins, is missing in Gotha, we do not know the exact total of drawings included in the thirty volumes splendidly bound in 1571, with Duke Albrecht’s portrait and arms impressed on their covers. At present, their number is close to 7,900; Prommer’s survey suggests that the Hadrianic coins numbered almost 600, in which case the grand total of drawings bound in the thirty volumes of the Magnum ac Novum Opus proper—the Gotha volumes—would have amounted to at least 8,500. This number implies that, between October 1566, when Prommer composed his Calculatio, and the actual binding in 1571, over eight hundred drawings were still added to the corpus. See here for a comparison of Prommer’s Calculatio with the volumes preserved.

Fickler's Inventory (1598)

The transcript given here is slightly adapted from the edition by Peter Diemer, Elke Bujok and Dorothea Diemer. This transcripts follows the finished manuscript, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, cgm 2133 (A), with annotations noting variants in the concept text, cgm 2134 (B). These annotations have not been preserved in the version presented below. The indications of the foliation of the two versions has been retained.

For the full version of the inventory: Johann Baptist Fickler, Das Inventar der Münchner herzoglichen Kunstkammer von 1598. Editionsband: Transkription der Inventarhandschrift cgm 2133. Herausgegeben von Peter Diemer in Zusammenarbeit mit Elke Bujok und Dorothea Diemer [= Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Abhandlungen, Neue Folge, Heft 125; vorgelegt von Willibald Sauerländer in der Sitzung vom 7. November 2003], München [Bayerischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften / C. H. Beck] 2004, pp. 41–43.

The transcription volume has since been complemented by a detailed annotated catalogue in 2 volumes, in which the objects mentioned in the inventory have been identified, and the context of their acquisition and later history added whenever possible, and a huge volume of essays :

Die Münchner Kunstkammer, Band 1: Katalog, Teil 1. Bearbeitet von Dorothea Diemer, Peter Diemer, Lorenz Seelig,Peter Volk, Brigitte Volk-Knüttel und anderen [= Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Abhandlungen, Neue Folge, Heft 129,1; vorgelegt von Willibald Sauerländer], München [Bayerischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften / C. H. Beck] 2008 (for the Strada volumes, see pp. 1–6).

Die Münchner Kunstkammer, Band 2: Katalog, Teil 2. Bearbeitet von Dorothea Diemer, Peter Diemer, Lorenz Seelig,Peter Volk, Brigitte Volk-Knüttel und anderen [= Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Abhandlungen, Neue Folge, Heft 129,2; vorgelegt von Willibald Sauerländer], München [Bayerischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften / C. H. Beck] 2008.

Die Münchner Kunstkammer, Band 3: Aufsätze und Anhänge. Bearbeitet von Dorothea Diemer, Peter Diemer etal. [= Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, Abhandlungen, Neue Folge, Heft 129,3; vorgelegt von Willibald Sauerländer], München [Bayerischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften / C. H. Beck] 2008.

Cyprian's Catalogue (1714)

Ernst Salomon Cyprian (1673–1745) was librarian of the Gotha Hofbibliothek. In 1714 he published a catalogue of its manuscripts, which included a description of the Magnum ac Novum Opus with some additional material, such as Veit Ludwig von Seckendorf’s earlier comments.

Cyprian gave a very brief description, and did not examine each individual volume; he moreover failed to spot that volume 15, including Hadrian’s coins, was already missing: though he mentions thirty volumes, only 29 catalogue numbers are in fact assigned to the Magnum ac Novum Opus. Cyprian describes Strada’s separate Series Imperatorum (Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek, Ms. Chart. A 1243a) as nr 31; he realizes that it is a separate work, and prints Strada’s preface in its entirety.

Ernst Salomon Cyprian, Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum Bibliothecae Gothanae, Leipzig 1714

<p. 83>

CCXXXIX.— CCLXIII.

Magnum ac novum opus continens descriptionem vitae, imaginum, numismatum omnium tam orientalium, quam occidentalium imp. ac tyrannorum, cum collegis, coniugibus liberisque suis, usque ad Carolum V. imperatorem, a IACOBO DE STRADA, Mantuano elaboratum. Anno Domini MDL. Volumina XXX I. dedicata hoc ipso anno clariss. & ampliss. Domino Ioanni IacoboFuggero in Kirchberg & Wissenhorn comiti.

De nostris codicibus in Licinio delinentibus iudicium tulit Struvius introductionis ad notitiam rei literariae cap. I. §. IX.

Inter cimelia rariora ( bibliothecae Gothanae ) adservantur aliquot Tomi Iacobi de Strada, in quibus rarissimi nummi Romani consulares & imperatorii stupendo labore & arte mirabili delineati sunt. Horum picturas singulas, singulis coronatis constitisse auctor est Occo in epistola Msta ad Amarbachium apud Patinum, in introdudione ad historiam numismatum cap.XXIV. p. 188. Similia in Caesaris Vindobonensi extare testatur Lambecius Bibliotheca Caes.Tom. I. p. 77.

Quid Seckendorffius de hoc opere, aut potius partibus eius prioribus, iudicarit, docebit lectores eius ad Bosium epistola, quam ex autographo adscribemus.

<…>

<p. 85>

Tomus XXXI. non pertinet ad ceteros codices, sed peculiare opus est primis XII. imperatoribus ex numis cognoscendis destinatum, cuius nos titulum & praefationem hoc loco exhibebimus.

Description from Boswell's Journal (1764)

James Boswell visits Gotha and inspects the Magnum ac Novum Opus

During his Grand Tour the Scottish nobleman, lawyer, men of letters James Boswell (1740–1795), later to became famous for his biography of Dr Johnson, visited Gotha, arriving at 16 October 1764, and leaving for Langensalza and Kassel on the 21st. He visited the Münzkabinett on Thursday 18th, and Ducal library on Fridat 19th October. For its charm, and to get a good impression of Boswell’s personality, and therefore the relative value of his very succinct description, we have included the full account of his visits to the Münzkabinett and the Hofbibliothek. It is cited from the reading or “trade” edition of the Yale edition of the Private Papers of James Boswell, vol. 4, omitting the notes: Frederick A. Pottle (ed.), Boswell on the Grand Tour: Germany and Switzerland 1764, New York / London 1953 [for the updated research edition, see: Marlies K. Danziger (ed.), James Boswell: The Journal of His German and Swiss Travels, 1764 [= The Yale Edition of the Private Papers of James Boswell / Research edition: Journal, Vol. I], New Haven 2008.

<p. 142–143> Boswell’s visit to the Münzkabinett

THURSDAY 18 OCTOBER. At twelve I went and saw the Duke’s cabinet of Medals. It is nobly arranged in cases with drawers in which are divisions for each medal. The heads of the emperors in plaster bronzed make a very suitable ornament to the cabinet. It contains about fifteen thousand pieces. It is very rich in Greek and Latin medals, and contains some very curious ones. There is here an Alexander the Great with his own head, and five pieces of Tiberius. The gentleman who has the care of the cabinet was very intelligent. Het told me that he could discover counterfeit antiques because the veritable antiques were round in the the edges, as anciently they coined in a different manner from what they do now. I found here also several English coins, and a few old Scots ones.

<…>

<p. 144–146> Boswell’s visit to the Gotha Hofbibliothek

FRIDAY 19 OCTOBER. I went and saw the Duke's Library, which is very large, in excellent order, and contains some curious pieces. There is a French book entitled La Truandise (i.e., in old French, pauvrete) de I'ame, where there is an allegorical picture of a poor soul which comes to receive from the Holy Church the alms of grace. The Soul is painted as a woman, stark naked, who presents herself before five or six sturdy priests and holds a bag to put their alms in. The book is in manuscript. There is also a German Bible which formerly belonged to the Elector of Bavaria. It is a manuscript written an age before the Reformation. It is in two volumes. The first contains the historical books of the Old Testament. It is probable that there has been another volume in which the rest of the Old Testament has been written. This first volume is decorated with paintings in an odd taste, but finely illuminated and richly gilded in the manner of that ancient art, which is now <p. 145> totally lost. Some of the designs are truly ludicrous. When Adam and Eve perceive that they are naked, God comes in the figure of an old man with a pair of breeches for Adam and a petticoat for Eve. One would almost imagine that the painter intended to laugh at the Scriptures. But in those days it was not the mode to mock at the religion of their country. The genius which is now employed to support infidelity was then employed to support piety. The imagination which now furnishes licentious sallies was then fertile in sacred emblems. Sometimes superstition rendered them extravagant, and sometimes weakness made them ridiculous, as I have now given an example. The second volume contains the New Testament complete. It is illuminated by the same hand as the first volume, as far as the history of Our Saviour's passion in the fourteenth chapter of St. Mark. It has been reckoned that the gold employed in illuminating the two volumes may amount to the value of a thousand ducats. It is probable that the ancient painter has died when he had got as far as the fourteenth of Mark. The Duke of Bavaria has however taken care that the work should not be left imperfect. At the end of this volume the arms of Bavaria are painted, and there is an inscription bearing that Otto Henry, Duke of Bavaria, caused the remaining part of the Sacred Oracles to be adorned by a more modern painter, anno 1530-1532 for it took two years to finish it. The work of the last painter has not the advantage to be illuminated with gold in the ancient manner, as was the work of the former painter. But the modern has been a much superior genius. His designs are remarkably well conceived, and executed with accuracy and taste. His colours are fresh and lively.

He has however now and then fallen into little absurdities. The Evangelist tells us that when Mary Magdalene found Our Saviour after his resurrection, she supposed him to be the gardener, for which reason the painter has drawn Christ holding a spade. Now Mary supposed him to be the gardener because he was in a garden. Had he had a spade in his hand, it was impossible to doubt of it. But how suppose that Jesus had a spade? Upon the whole, this Bible is one of the noblest books that I have ever seen.

<p. 146> There is here another remarkable book, Magnum opus continens numismata imperatorum Romanorum, a Jacobo de Strada Mantuano elaboratum, anno 150-.* This work was executed by order of the Count de Fugger, whose family was in Germany what the family of the Medici was in Italy. The work consists of thirty-one volumes, in each of which is from 300 to 500 leaves. For each leaf the Count de Fugger paid a ducat, so that at the least it must have cost 9,300 ducats. It would seem that there have been more copies of this work, for some of the first volumes are to be found in the Libraries of Vienna and Dresden. The library-keeper at Gotha is a very learned man, simple, quiet, and obliging.

I was this day dressed in a suit of flowered velvet of five colours. I had designed to put on this suit first at Saxe-Gotha. I did so. It is curious, but I had here the very train of ideas which I expected to have. At night the Princess made me come to the table where she sat at cards, and said, "Mr. Boswell! Why, how fine you are!"** She is a good, lively girl. I am already treated here with much ease. My time passes pleasantly on. Between dinner and evening court I read the Nouvelle Heloise; write; I think.

* "An extended study of the medals of the Roman Emperors, made by Jacopo de Strada of Mantua, in the year 150-."

** The memoranda, however, show that the Princess [= Friederike Louise of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg] advised Boswell to put on a black ribbon and to wear a different sword-knot.