Who was Jacopo Strada?

Jacopo Strada (Mantua 1515- Vienna 1588) was born into a patrician family of Mantua. His father was an official in the administration of the Gonzaga dukedom: his son’s intelligence, interest in antiquity, and artistic talents probably recommended him to members of the dynasty, in particular to Isabella d’Este. He received a humanist education in the ambit of the Gonzaga court, as well as –more unusual– an artistic training in workshop of Giulio Romano, Raphael’s pupil who had become the Gonzaga’s principal architect and artist. Giulio imparted his knowledge and experience of the antique to his young pupil, together with the method of studying the antique and adapting its examples to contemporary artistic projects developed in Raphael’s circle.

This included the study of ancient coins, of which Giulio himself owned a collection considerable both in quantity and quality. Strada developed foremost into an antiquary, both studying and dealing antique objects, as well as documenting these both for his own use, and on behalf of his patrons or customers. In his youth he travelled widely in Italy and in France to study the antique and probably also to build up a network of both intellectual friends and commercial relations. At the latest by 1544 he lived in Nuremberg, where he remained for several years and was amplifying his collections of antiquities as well as contemporary works of art, among which a huge collection of Dürer prints. But he had come to Germany earlier, since he married a German noblewoman, Ottilie Schenk von Rossberg from Würzburg, in that same year.

By that time he was regularly employed by his most important early patron, Hans Jacob Fugger, who possibly had met Strada already in Italy, when he studied Roman law at the University of Bologna. Fugger supported many artists and scholars, and he prized Strada’s antiquarian expertise sufficiently to finance his trips in Germany, Italy and France to collect and study ancient coins, and not just to obtain originals for Fugger’s collection, but also to document those he could not acquire.

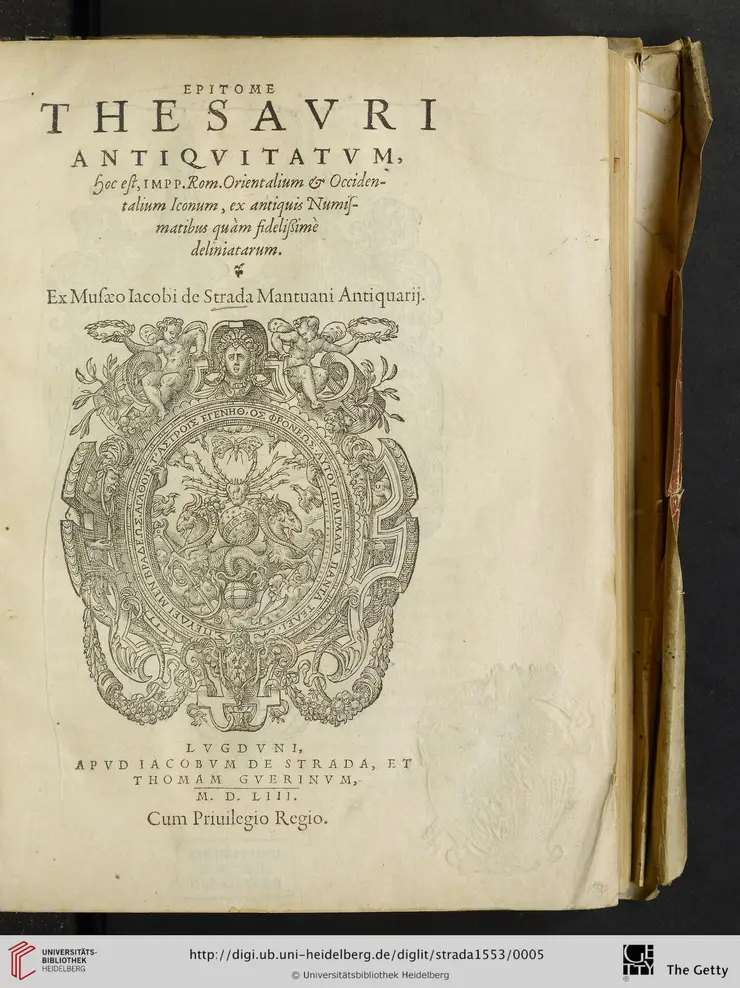

The first result of this was Strada’s Epitome Thesauri antiquitatum (Lyon 1553), dedicated to Fugger, containing extensive lives of all Roman Emperors from Julius Caesar up to the reigning Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. This book also included a woodcut likeness of each emperor and of many of their relatives taken from the obverses of ancient Roman imperial coins, as well as a description of both obverse and reverse of the relevant coin.

In addition, from 1550 onward at the latest , Strada used the numismatic documentation he had collected to prepare a corpus of ancient coins, consisting of two separate but related works: a series of drawings of coins of the Roman emperors, the Magnum ac Novum Opus continens descriptionem Vitae, imaginum, numismatum omnium tam Orientalium quam Occidentalium Imperatorum <…> usque ad Carolum V. Imperatoremand a systematic collection of structured, succinct descriptions of both Roman imperial and of other ancient coins, the A[ureum) ∙ A[rgenteum] ∙ A[ereum] numismatωn antiquorum ΔΙAΣΚΕΥΗ.

The object of our project was to study these two works in conjunction.

The Magnum ac Novum Opus was certainly destined for Hans Jakob Fugger, to whom its first volume (dated 1550) is dedicated. It was not an exclusive commission: several other volumes of similar numismatic drawings have been preserved elsewhere, some of them dedicated to the Emperors Ferdinand I and Maximilian II.

Though it seems likely that Fugger would have wished to have the documentation belonging to the drawings in the Magnum ac Novum Opus he had commissioned, there is only circumstantial evidence that he ever owned a copy of the ΔΙAΣΚΕΥΗ. The various later copies of another numismatic work produced in Strada’s workshop, the Series Imperatorum ∙ romanorum∙ ac graeorum et germanorum omnium, show that text and images were at least intended to be combined.

Thanks to his talents, but also to Fugger’s patronage and his huge network, Strada’s career prospered: after his trips to Lyon, Rome and Venice in the early 1550s, he obtained the patronage of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, and by the end of the decade had established himself as Imperial architect and antiquary, working both for the house of Austria itself, and for members of their court. He remained active as an agent for Fugger, and continued to do so after Fugger had moved to Munich to enter the service of his close friend, Albrecht V, Duke of Bavaria, who had taken over Fugger’s collections and library -including the Magnum ac Novum Opus- in exchange for settling Fugger’s debts.

Thus Strada became involved in various commissions for the Duke, primarily the acquisition of antiquities in Venice. It was at this time that the aged Titian painted his famous portrait of Strada still preserved in Vienna. To house both library and antiques, Strada created the concept for the Antiquarium of the Munich Residenz, for which he made an elegant and practical Italianate design which was realized in a more vernacular manner by the Augsburg master mason Simon Zwitzl.

As Fugger’s associate and probably business partner, Strada had become rich enough to build a town palace in Viena that served as an object lesson of Italian architecture in the classical manner of Raphael and Giulio, as well as promoting his own expertise, and the cultural goods he promoted and sold.

Among these were a number of profusely illustrated publications on historical, antiquarian and artistic themes, such as Onofrio Panvinio’s edition of the Fasti Capitolini (Venice 1558), and illustrated edition of Caesar’s Commentaries, and the Seventh Book of Sebastiano Serlio’s architectural treatise (both Frankfurt 1575). The remainder of his megalomaniac publication programme, including a huge illustrated dictionary or rather encyclopaedia in ten-languages, never materialized.

In 1579 Strada resigned as antiquary to Emperor Rudolf II, who replaced him by his son Ottavio Strada da Rosberg. Strada, whose wife had predeceased him died in Vienna in November of 1588. His Nachlass was repeatedly drawn uponfor new publications both by Ottavio Strada, and by the latter’s son, Ottavio II Strada da Rosberg.