How do you write a book? Mark Porter on the writing process of his new book "For the Warming of the Earth"

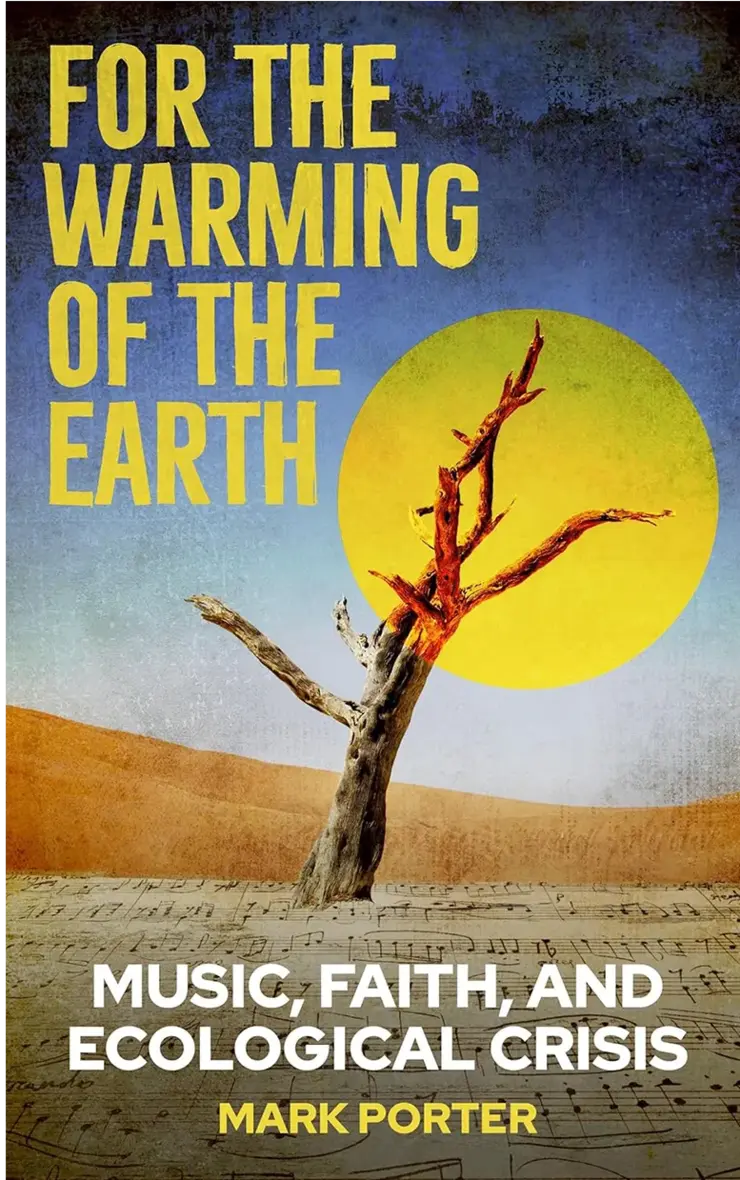

In June 2024, Mark Porter, who works as a senior lecturer at our Chair of Fundamental Theology and Religious Studies will publish his new book "For the Warming of the Earth”. The book asks to what extent our religious practices are changing in the face of the climate crisis and how we can respond to this crisis with the help of music and liturgy. We spoke to Mark about how the text came about and what he recommends as an antidote to writer's block.

How did you come up with the idea for your current book? And did you know right away that it would have been a bigger publication, or did it just turn out to be a book at some point during the process?

It’s a project that emerged in several stages. Initially there was a kind of curiosity about something that was happening in the world, that different Christian communities seemed to be responding to the climate crisis in different ways, and many of them were using music in order to do so. That led to a couple of conversations with different musicians to figure out whether there might be anything to write about here. Those conversations led to more conversations, and after I’d carried out a certain number of interviews, I began to feel a sort of responsibility to the people I’d interviewed to write up some of what I’d found out in the form of an article.

As a result of the temporary nature of early career academic contracts, I was unemployed at this point, and not particularly sure whether any of this research could really turn into a bigger project, but I figured I’d put together a funding application. Writing the application helped me to structure some of my ideas and get an idea as to what some kind of bigger project might end up looking like, but despite the positive recommendations of all the reviewers, the funding organisation decided not to fund the project.

I can’t remember exactly when it was, but at some point, I essentially thought “sod them, I’ll do the research anyway”, and I set up a basic template where I could slowly begin to develop some of my thoughts and ideas.

I think I was about halfway through the writing process when someone thankfully took pity on me and offered me a job. That gave me the opportunity to really focus some time on finishing the project. Once I’d got a few of the chapters drafted, I sent a very very rough version of what I’d put together to an editor who told me that yes, in theory this might be something they would be interested in. It was only once I’d finished a complete first draft that I put together a formal proposal and, thankfully, they decided that it was a project that would be worth publishing for a wider audience.

We often think of writing as quite a lonely and isolated activity. Does field work, doing interviews and talking to people make the writing process itself feel a bit more interactive?

Very much so. In fact this was one of the main things that brought me back to academia after some time away working in other kinds of environment. I just couldn’t imagine spending most of my time alone with books, reading and writing. I was pretty sure that would drive me crazy. Spending so much of the research process talking to people about their lives, finding out about the things that are important to them, and then writing in dialogue with these different voices when I put an article or book means not just that I feel a little bit less isolated, but that my work carries a kind of personal significance with it. Engaging in those conversations is a massive part of what makes my work feel meaningful. I highly recommend it.

How has your writing style changed and developed over time?

In a lot of ways, I’m not a very natural writer. At school, English was pretty much my worst subject, and at university my tutors would constantly complain that my essays were too short and that I needed to make them longer. Some of that has stayed with me, I still tend to write books a little on the shorter side, but for the average reader that’s often not a bad thing. Very few people want to read a 500 page academic book.

Writing is something I’ve honed in lots of different ways over the course of time through little projects such as blogging and poetry-writing, through proof-reading of other people’s texts, and of course through writing my own pieces. When I first set about a major writing project as part of my doctoral research, it took me a while to find a voice and a way of writing that worked for me. Really, what I have now is a mixture of storytelling, commentary, and theory.

My own personal experiences often serve as a doorway into a project, helping other people to relate to what I’m trying to write about, but the main core of ethnographic writing is often about drawing together the voices and experiences of a range of different individuals and letting them come through in a way that means my own voice sometimes fades a little more into the background.

Writing for me now is often about juggling those different elements alongside academic theories and reflection until the balance feels just about right and feels like it tells a story that offers some useful insights along the way.

The internet is full of advice for getting over writer's block: Do you have any particular advice that's a bit different from what's commonly given?

Like many writers, I’m often good at avoiding writing. Putting ideas on the page, and going back and reading what I’ve written is a process that fills me with all kinds of anxiety and self-doubt. I wonder whether my ideas are any good, whether they’re readable and whether I can really shape an entire project into a form that makes sense and which anyone would want to read.

It often takes a fair amount of psyching myself up in order to confront that process and bring myself to a point where I have enough confidence in what I’m doing to make the next steps.

There are a few things that have helped me over the years. I realised early on that a rhythm of reading in the mornings writing in the afternoons seemed to work quite well for me. That way I soak up lots of ideas from other people over the early part of the day which can help to inspire me when I put my own fingers to the keyboard in the afternoon.

Alongside that it’s often a matter of breaking something down into smaller tasks and smaller targets that mean I don’t have to confront the whole project at the same time. I told myself early on that I should aim to write 1,000 words a day and that they didn’t have to be good words, but they had to be on the page. For me one of the big psychological hurdles is the sheer length of a big project, and if I have 70,000 mediocre words on the page that I can work on and refine, that’s often easier for me than trying to produce 70,000 perfect words the first time around.

At later stages it's often a matter of reading through my text and writing little annotations about what I don’t like. I separate the work of finding the problems from the work of fixing them so I don’t have to do both at once. Once I’ve got a couple of hundred comments about the different things I need to fix, I again set myself little daily targets as to how many I’m going to work on at any given time – often starting with the easier ones and working my way through to the ones that require a little more thought when there aren’t quite so many left to deal with. These are very simple things, but they’re really about reducing those psychological barriers so that every little step feels a little bit more manageable.

Coming back to your book: the title “For the Warming of the Earth” is very beautiful. Do you remember the moment when you came up with it?

For me, the title is often one of the last parts of a project to come together. I begin working on a research project with a fairly technical working title that is never going to appeal to an audience, but which describes the project well enough for the purposes of funding applications and presentations. The title often arrives relatively near the end of the process as I’m trying to think about something that might appeal to a wider public.

In this case, if I remember correctly, I was playing with lots of different possibilities in my head as I was walking through the countryside. It often works like that, just trying out different combinations of words, different allusions you can make, different arrangements of a sentence. There’s a traditional hymn called “For the beauty of the earth”, and I experimented with a few different variations of this title in my head before settling on this one. As with a lot of things, I wasn’t quite sure first of all whether it was really what I wanted to go for, but then it just sort of settled and felt right. The idea is to point to a well-known hymn that celebrates the wonders of creation and to say that some of that simple celebration probably needs to look a little bit different right now in light of our current ecological crisis.

You can find more information on the book here: